SS London (1864) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SS ''London'' was a British

The final voyage of the ''London'' began on 13 December 1865, when the ship left Gravesend in Kent bound for Melbourne, under a Captain Martin, an experienced Australian navigator. A story later highly publicised after the loss states that when the ship was en route down the Thames, a seaman seeing her pass

The final voyage of the ''London'' began on 13 December 1865, when the ship left Gravesend in Kent bound for Melbourne, under a Captain Martin, an experienced Australian navigator. A story later highly publicised after the loss states that when the ship was en route down the Thames, a seaman seeing her pass

Three main factors were attributed to the sinking of ''London'' by the subsequent inquiry by the

Three main factors were attributed to the sinking of ''London'' by the subsequent inquiry by the

*John Debenham, son of William Debenham, founder of Debenham and Freebody's department stores

*

*John Debenham, son of William Debenham, founder of Debenham and Freebody's department stores

*

S.S._''London''_-_founded_[sic:__foundered

/nowiki>_in_the_English_Channel.html" ;"title="ic: foundered">S.S. ''London'' - founded[sic: foundered

/nowiki> in the English Channel">ic: foundered">S.S. ''London'' - founded[sic: foundered

/nowiki> in the English Channelnewspaper excerpts of the sinking and McGonagall's poem at rootsweb.com * The last chapter describes the ship's final voyage in some detail * {{DEFAULTSORT:London Shipwrecks in the Bay of Biscay Maritime incidents in January 1866 1866 in the United Kingdom Steamships Passenger ships of the United Kingdom Ships built by the Blackwall Yard 1864 ships

steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamship ...

that sank in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

on 11 January 1866. The ship was travelling from Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Rochester, it is ...

in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

to Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, when she began taking in water on 10 January, with 239 persons aboard. The ship was overloaded with cargo, and thus unseaworthy, and only 19 survivors were able to escape the foundering ship by lifeboat, leaving a death toll of 220.

History

''London'' was built inBlackwall Yard

Blackwall Yard is a small body of water that used to be a shipyard on the River Thames in Blackwall, engaged in ship building and later ship repairs for over 350 years. The yard closed in 1987.

History

East India Company

Blackwall was a sh ...

by Money Wigram and Sons and launched on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

on 20 July 1864, and had a 1652-ton register.

From 23 September 1864, she undertook sea trials and on 23 October 1864 started her first voyage to Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

via Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

. During the voyage, a boat crew was sent to locate a man overboard, but this boat crew was lost, and later rescued by the ''Henry Tabar''. ''London'' arrived in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

on 5 December 1864 and set sail again on 7 December, arriving in Melbourne on 2 January 1865.

On 4 February 1865, she left Melbourne for the return trip to London with 260 passengers and 2,799.3 kg of gold, and arrived back in Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Rochester, it is ...

on 26 April 1865.

A second trip to Melbourne started at the end of May 1865, and she arrived on 4 August. She departed on 9 September 1865 for the return trip with 160 passengers and 2,657.5 kg of gold, arriving back in London in November of that year.

Sinking

The final voyage of the ''London'' began on 13 December 1865, when the ship left Gravesend in Kent bound for Melbourne, under a Captain Martin, an experienced Australian navigator. A story later highly publicised after the loss states that when the ship was en route down the Thames, a seaman seeing her pass

The final voyage of the ''London'' began on 13 December 1865, when the ship left Gravesend in Kent bound for Melbourne, under a Captain Martin, an experienced Australian navigator. A story later highly publicised after the loss states that when the ship was en route down the Thames, a seaman seeing her pass Purfleet

Purfleet-on-Thames is a town in the Thurrock unitary authority, Essex, England. It is bordered by the A13 road to the north and the River Thames to the south and is within the easternmost part of the M25 motorway but just outside the Greater Lon ...

said: "It'll be her last voyage…she is too low down in the water, she'll never rise to a stiff sea." This proved all too accurate.

The ship was due to take on passengers from Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

, but was caught in heavy weather, and the captain decided to take refuge at Spithead near Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

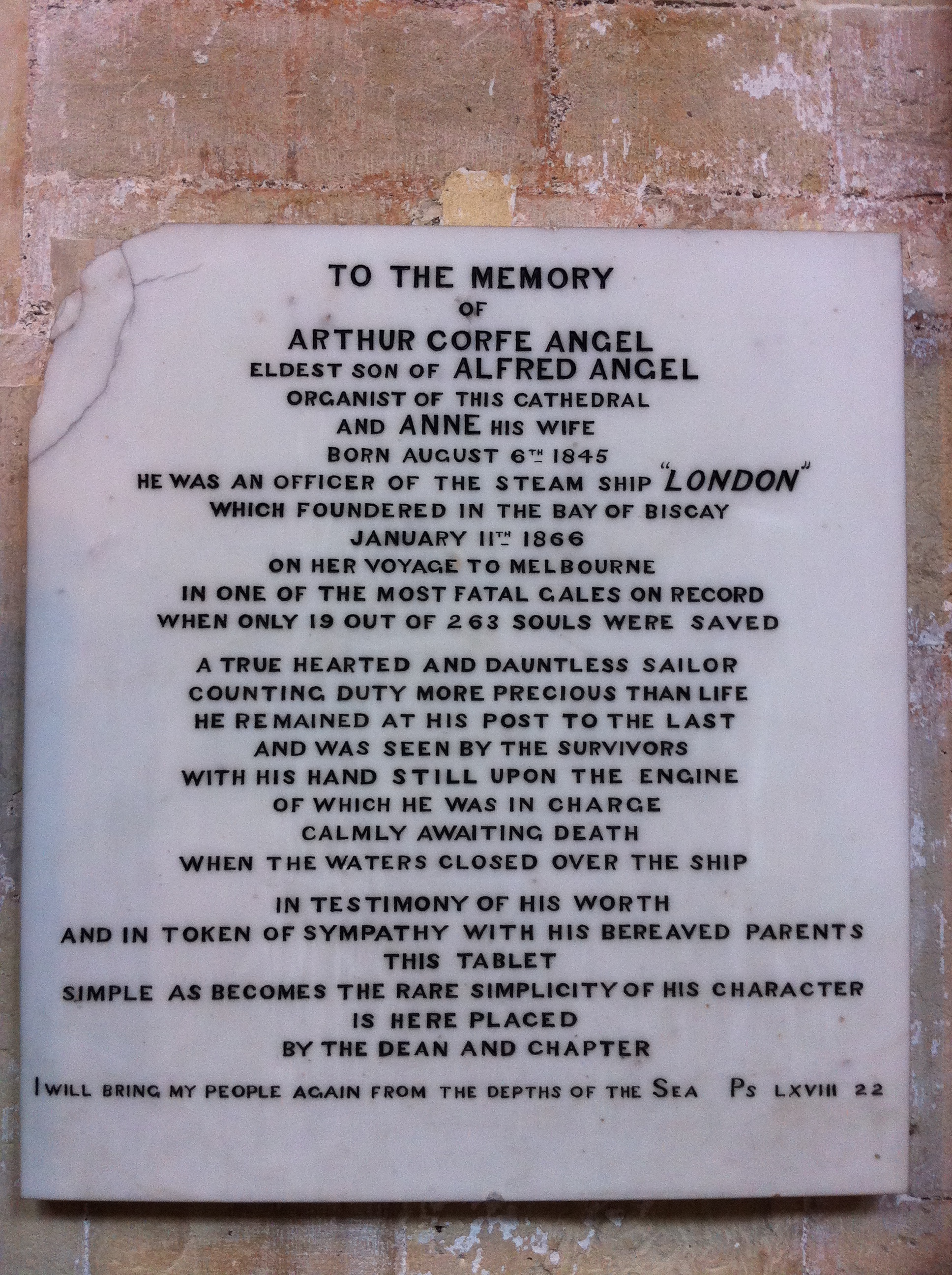

. The ''London'' eventually docked in Plymouth. The ship then restarted the journey to Australia on 6 January 1866. There were 263 passengers and crew aboard, including six stowaways. On the third day out while crossing the Bay of Biscay in heavy seas the cargo shifted and her scuppers choked, forcing the vessel lower in the water where she was swept by tremendous seas. Water poured down the cargo hatches extinguishing her fires and forcing the captain to turn about and return once more toward Plymouth. In so doing he headed into the eye of a storm. On 10 January, after a considerable buffeting over several days, a sea carried away the port life boat; then at noon another wave carried away the jib-boom, followed by the fore topmost and main royalmast with all spars and gear. On 11 January a huge wave crashed on deck, smashing the engine hatch which resulted in water entering the engine room putting the fires out. By 12 January her channels were nearly level with the sea and a decision was made to abandon ship. The life boats were swamped as soon as launched, with only one craft staying afloat. Nineteen people escaped on the life boat, only three of whom were passengers. When the boat was a hundred yards away from the ship, the ''London'' went down, stern first. As she sank, all those on deck were driven forward by the overpowering rush of air from below, her bows rose high till her keel was visible and then she was "swallowed up, for ever, in a whirlpool of confounding waters". The ''London'' took with her two hundred and forty-four persons. It was reported that the last thing heard from the doomed ship was the hymn "Rock of Ages Rock of Ages may refer to:

Films

* ''Rock of Ages'' (1918 film), a British silent film by Bertram Phillips

* ''Rock of Ages'' (2012 film), a film adaptation of the jukebox musical (see below)

Music

* ''Rock of Ages'' (musical), a 2006 rock ...

". The nineteen people who got away in her cutter were the only ones saved. They were picked up next day by the barque ''Marianople'' and landed at Falmouth.

''The Wreck of the Steamer 'London' while on her way to Australia'' is a poem by Scottish poet William McGonagall

William Topaz McGonagall (March 1825 – 29 September 1902) was a Scottish poet of Irish descent. He gained notoriety as an extremely bad poet who exhibited no recognition of, or concern for, his peers' opinions of his work.

He wrote about 2 ...

, one of his many poems based on disasters of the time.

Causes

Three main factors were attributed to the sinking of ''London'' by the subsequent inquiry by the

Three main factors were attributed to the sinking of ''London'' by the subsequent inquiry by the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

: firstly, the decision by Captain Martin to return to Plymouth, as it is believed the ship had passed the worst of the weather conditions and by turning back the ''London'' re-entered the storm; secondly, the ship was overloaded with 345 tons of railway iron; and finally, the 50 tons of coal which was stored above deck, which after the decks were washed by waves blocked the scupper

A scupper is an opening in the side walls of a vessel or an open-air structure, which allows water to drain instead of pooling within the bulwark or gunwales of a vessel, or within the curbing or walls of a building.

There are two main kinds of s ...

holes, which prevented drainage of the seawater.

Messages in bottles found

According to a publication out of Hamilton, Victoria, Australia, messages in bottles that originated with people who were lost in this sinking were found. From the Hamilton Spectator (Page 3, 12 May 1866): "The ''Argus'' contains an account of certain bottles found on the French coast of the terrible Bay of Biscay." A retelling of this account reveals that the bottles contained "farewell messages from passengers by the London to friends and relatives in England." According to one D.W. Lemmon, presumed drowned: "The ship is sinking," he wrote, "no hope of being saved." Mr. H.F.D. Denis wrote "Adieu, father, brothers and sisters, and my dear Edith. Steamer London, Bay of Biscay. Ship too heavily laden for its size, and too crank. Windows stove in. Water coming in everywhere. God bless my poor orphans. Storm not too violent for a ship in good condition."Diamonds lost

In hismonograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

"Governor Phillip in Retirement" Frederick Chapman, whose mother, two brothers, and a sister died in the wreck, wrote as follows:In December865 __NOTOC__ Year 865 ( DCCCLXV) was a common year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. Events By place Europe * King Louis the German divides the East Frankish Kingdom among his three sons. C ...my mother opened out to my amazed eyes such a mass of diamonds as I had never seen before. This was the property which "Aunt Powell" had left or given to her niece my Great-Aunt Fanny, who at the age of ninety-one had given them to my mother, the wife of her nearest heir. Less than a month later (11th January 1866) the disastrous foundering of the S.S. London carried this collection to the depths of the Bay of Biscay. In that disaster perished my mother, my eldest and youngest brothers, my only sister, and many of our friends.

Legacy

The loss of the ''London'' increased attention in Britain to the dangerous condition of thecoffin ships

A coffin ship () was any of the ships that carried Irish immigrants escaping the Great Irish Famine and Highlanders displaced by the Highland Clearances.

Coffin ships carrying emigrants, crowded and disease-ridden, with poor access to foo ...

, overloaded by unscrupulous ship owners, and the publicity had a major role in Samuel Plimsoll

Samuel Plimsoll (10 February 1824 – 3 June 1898) was a British politician and social reformer, now best remembered for having devised the Plimsoll line (a line on a ship's hull indicating the maximum safe draught, and therefore the minimum fr ...

's campaign to reform shipping so as to prevent further such disasters. The disaster helped stimulate Parliament to establish the famous Plimsoll line

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

, although it took many years.

Notable deaths

*John Debenham, son of William Debenham, founder of Debenham and Freebody's department stores

*

*John Debenham, son of William Debenham, founder of Debenham and Freebody's department stores

*Gustavus Vaughan Brooke

Gustavus Vaughan Brooke (25 April 1818 – 11 January 1866), commonly referred to as G. V. Brooke, was an Irish stage actor who enjoyed success in Ireland, England and Australia.

Early life

Brooke was born in Dublin, Ireland, the eldest son of ...

, Irish stage actor

*Thomas Maxwell Tennant, Bowershall Engine Works, Leith (buried in Grange cemetery, Edinburgh)

*James and Elizabeth (née Fly) Bevan, parents of the first Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

rugby union captain James Bevan

* John Woolley, first principal of the University of Sydney, Australia

*Rev. Daniel James Draper, Methodist missionary, and his wife, Elizabeth Shelley Draper

*Catherine Brewer Chapman and three children, Henry Brewer Chapman born 10 April 1841, Catherine Ann Chapman born 18 October 1850 and Walter George Constantine Chapman born 12 July 1852, the wife and three children of Henry Samuel Chapman

Henry Samuel Chapman (21 July 1803 – 27 December 1881) was an Australian and New Zealand judge, colonial secretary, attorney-general, journalist and politician.

Early life

Chapman was born at Kennington, London, the son of Henry Chapman, Engl ...

, first puisne judge

A puisne judge or puisne justice (; from french: puisné or ; , 'since, later' + , 'born', i.e. 'junior') is a dated term for an ordinary judge or a judge of lesser rank of a particular court. Use

The term is used almost exclusively in common law ...

in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, former Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sepa ...

, Attorney General of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, Member of the Victorian Parliament

The Parliament of Victoria is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of Victoria that follows a Westminster-derived parliamentary system. It consists of the King, represented by the Governor of Victoria, the Legislative Assembly and ...

and responsible for the introduction of the secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

.

Notes

Further reading

S.S._''London''_-_founded_

/nowiki>_in_the_English_Channel.html" ;"title="ic: foundered">S.S. ''London'' - founded

/nowiki> in the English Channel">ic: foundered">S.S. ''London'' - founded

/nowiki> in the English Channelnewspaper excerpts of the sinking and McGonagall's poem at rootsweb.com * The last chapter describes the ship's final voyage in some detail * {{DEFAULTSORT:London Shipwrecks in the Bay of Biscay Maritime incidents in January 1866 1866 in the United Kingdom Steamships Passenger ships of the United Kingdom Ships built by the Blackwall Yard 1864 ships